We have all been there — that interview where you felt you aced every question, crafted a solution to a case study, and left with a feeling of genuine optimism. The handshakes were firm, the smiles warm, and the future, seemingly bright. Then, the email arrives. Polite, professional, and utterly deflating: “We’ve decided to pursue another candidate”.

For me, one particular rejection from my younger days still occasionally surfaces, a ghost my professional memory of the past. The company was in communications planning and data analytics, a field I was — and still am — deeply passionate about. I felt the interview went exceptionally well. I tackled their case study on the spot, confident I had presented a genuinely novel, thought-out solution. All signs pointed to success.

But the dreaded email — “Sorry, we are not progressing with our discussions with you” — came a few days later.

I would find out later from a friend who was working there was a little baffling as it was not about lack of skill, experience, or even motivation. It was something far more enigmatic: I apparently did not have the “killer instinct”.

To say I was baffled would be an understatement. What is the “killer instinct”? What does it truly mean to possess it, especially in the context of a strategic, data-driven role?

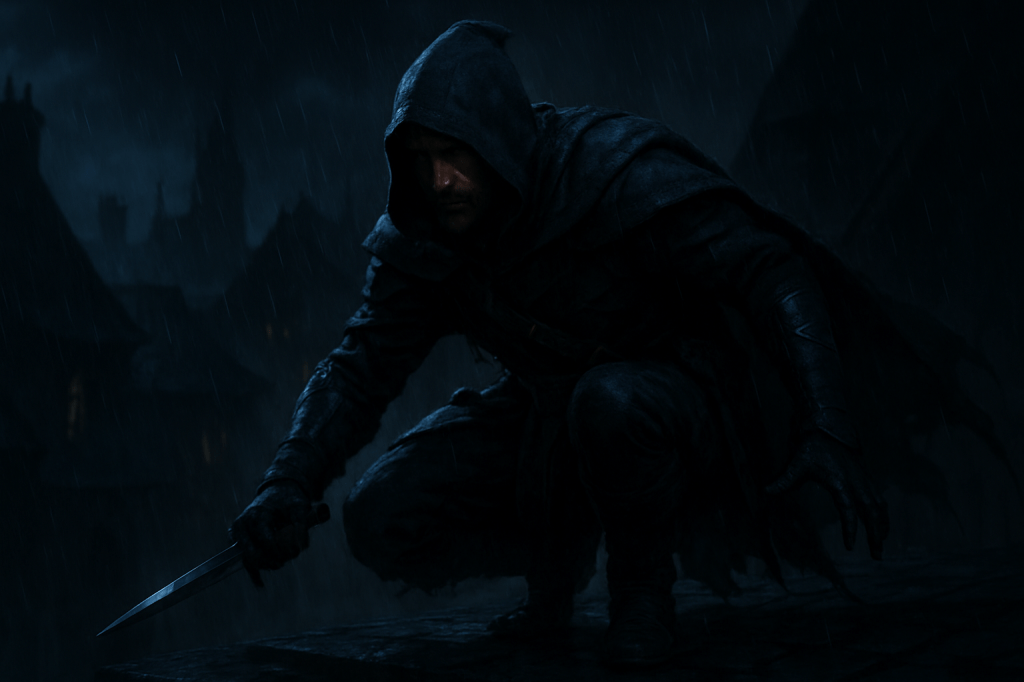

When I hear “killer instinct“, images of high-stakes negotiations, aggressive sales tactics, or ruthless corporate takeovers spring to mind. They also conjure up images of rampant office politics and essentially, highly-driven executives who are aggressively pursuing career advancement regardless of the means of getting to the top.

For me, “killer instinct” always did carry a darker, more predatory undertone for me.

And I am not alone in thinking that: Even the Cambridge Dictionary defined it as:

“a way of behaving in order to achieve an advantage for yourself without considering or worrying if it hurts other people”

In Spanish, the translation is even more sinister-sounding: instinto asesino.

If that definition were indeed of “killer instinct”, then I certainly did not have it.

Sure, I had been aiming for the progression and development back when I was younger. I wanted to be respected as an expert in data and analytics. I wanted to be heard in meetings. I wanted my opinions to be listened to and my solutions seriously considered for problems that I have been roped in to solve. And I wanted to be promoted and have yearly salary increments and bonuses.

But in dreaming of all these, I never wanted to step on someone else.

I knew back then — and now — that to progress, I need not step on other people. I believed in teamwork. I believed in working with integrity — doing the right thing even when no one is looking. I believed that individual growth does not come from stunting, demeaning, and sacrificing others. I believed — and still believe — in a kind of leadership that listens, that is inclusive, and that seeks to grow as others grow.

This led me to think: “In not getting that assignment, I did dodge a bullet.”

What kind of a company, I asked then and I still ask now, would genuinely require its employees — and its leaders — to embody such an ethos: To advance their careers through the subjugation, sacrifice, or detriment of others?

My career has shown me that true success — particularly in the complex and collaborative world of marketing strategy, data, technology, and insights — comes not from stepping on others.

True success from lifting them others up, empowering teams, and fostering an environment where collective intelligence and personal excellence thrive harmoniously.

True success comes from leveraging data and analytics to create shared dreams, shared objectives, shared values — not to exploit people’s weaknesses.

The memory of the rejection still comes back once in a while.

But more than a pining for what could have been, I look back at this scenario as me dodging a real bullet.

Had I joined that company, I know I would survive: But will I like the person I would have become if I decided to play their games in search for that “killer instinct”?

I probably would not.

So. As I always say, all is well that ends well.

And I am grateful that I was judged to be lacking of killer instincts back then.

Leave a comment